On shootings

Shootings are traumatic for all involved, and it is important that they be analyzed after the fact. Of course, when judging this kind of event after the fact, we spend hours or days analyzing a situation where the original events required an analysis and a decision within seconds.

One fact that is often dissected by the public is the number of shots fired. As an example, in the recent unfortunate Sean Bell shooting here in New York City, one officer fired 31 rounds. Was this too many? While common sense might seem to say yes, we would contend that the only shot that needs deep analysis is the first, and that when shootings involve multiple shooters, the total number of shots fired will almost always be surprisingly high.

Several factors enter into play. The first is that under stress you are reacting very quickly and in a very goal-oriented (stay alive) mode. Because of this, there is a real and strong tendency to shoot until you are aware that the threat has diminished or that you have run out of ammunition. Now, let us assume that an incident starts and ends over a fairly extended period of time, say, ten seconds from the time the first shot is fired. Now, how fast you can shoot depends on the kind of gun you have. Revolvers can shoot very fast but only hold six rounds, while semi-automatic handguns are slower but hold more cartridges.

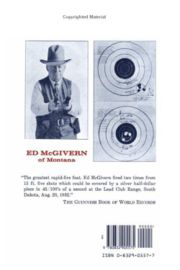

How fast is fast? Well, back in 1932 Ed McGivern was able to place five shots from 15 feet, with a spread that could be covered by a half dollar, in 0.45 seconds. In 2003 Jerry Miculek fired five shots in 0.57 seconds, close to McGivern’s 0.45, but broke McGivern’s record of shooting six shots each from 10 different .38 caliber revolvers in 25 seconds, shooting his sixty shots in 20 seconds. You can see some of Miculek’s shooting at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=giSaNiQ-Wb4.

So, what happens is that everyone is all keyed up, with adrenalin flowing, and someone fires a first shot. Often nobody knows who exactly fired the shot or what triggered the response that caused them to pull the trigger. There is no time to reflect on this: Someone yells “gun,” a shot is fired, and everyone instinctively starts shooting. This is known unofficially as the popcorn effect, and more officially as mass reflexive response. On a good day about a third of the shots hit the person at whom you are shooting. For those not mathematically inclined, this means that two thirds of the shots miss the target, explaining our belief that we are not concerned with the bullet that has our name on it: We are afraid of the bullet that says, “To whom it may concern!”

Because of the stress and the time constraints, and assuming that you yourself have not been shot, you tend to shoot until you become aware that you have run out of ammunition. If you are well-trained, you may not even be consciously aware that you have re-loaded and continued firing. It is simply unnatural for anyone, when they believe they are being shot at, to stop shooting before they are aware that the threat has ended. This does not take away responsibility for what happens to the rounds that fly off to hit some innocent after missing the target. And, more to the point, it does not take away responsibility for the first shot. This includes situational responsibility.

What is situational responsibility? Let us go back to what is needed to justify hurting (which can cover a wide range, up to and including killing) someone:

• Ability: Could the assailant hurt you? (He has a club.)

•Opportunity: Can the ability be put to use on you? (His ability is less if he is on the other side of the street with the club, greater if he is on your side of the street coming toward you.)

• Jeopardy: Is there reason for you to believe you are in actual danger? (If the club is a baseball bat and he also has a bag of softballs your sense of danger should be less than if he has a bat and is screaming that he is going to beat your brains in.)

• Preclusion: What steps did you take to keep the conflict from starting, from continuing, and to get away from the conflict? (If he says “Your mother wears army boots” and you snap back “So’s your old man,” you have become a willing participant in moving the conflict to the next level.)

• Reasonableness: Was the amount of force you used reasonable for the threat that you faced? (Shooting someone who pies you will most likely be seen as excessive.) It is the last two items that are the ones likely to get a civilian sent to jail, and get a police precinct picketed by the Reverend Al Sharpton. In most questionable shootings what is questionable is not the tactics or the execution of force, but the fact that it happened at all – that is to say, in the planning and supervision, not in the execution of the plan. Thus, if in a police shooting the first three criteria are met, the officers will reasonably be acquitted, because the supervision and planning – the last two criteria – were not within their purview. Because of this, when prudent police departments analyze what happened, they should not (in a more-perfect world) concentrate on the shooting issues (like the number of shots fired), but rather on how the situation could have been prevented, and how similar instances can be prevented in the future, all of which are supervisory issues.

Civilians who carry guns don’t act under color of law, and don’t have preclusion and reasonableness separated from ability, opportunity, and jeopardy. This is a very big difference! For civilians, therefore, real thought must be given to how best to avoid getting into a situation where a gun is needed. The civilian must attempt to de-escalate any situation that can be deescalated before it turns into shots fired by anyone connected to the event. If the civilian’s aim is true, the difference is between Murder and Self Defense.