Religion-related terrorism

As noted in the first article, most of what today passes for terrorism is merely an unfortunate byproduct of religion, which means we need to discuss why factors relating to religion are causing such problems. We need to do so because so much public policy, and so many costs, both financial and social, depends on our understanding the issues.

We will deal with this issue in two parts. The first part will deal with the conflict between religion and civil society – between morality and ethics. The second part will deal with the underlying theological relationships between religion and violence. Those who have no interest in theology can skip the second part, though we believe it to be interesting and useful.

The conflict between religion and civil society

Morality versus ethics

While in many cases scriptural law (morality) and natural law (ethics) overlap, in some cases they don’t. Thus, some Muslims and Jews say it is immoral to eat pork. The ethical view of this, as wittily expressed by Woody Allen, was that the Bible (and by extension the Qur‘an) probably didn’t mean to say you shouldn’t eat pork: They most likely meant that you shouldn’t eat pork in certain restaurants… (A discussion of the historicity of not eating pork can be found in the November 2004 AEGIS.)

The issue of morality is a difficult one largely because each person believes that he or she is the keeper of the Truth, and that others are not.

Violence from religion

Religious views can have a distinct effect on civil society. We saw this some little time ago when we did jury duty on an alleged DUI case. The judge explained to the jury pool that she would explain the law to us, and that our job was to interpret the testimony based on that interpretation. One of the jurors said that she was a Christian, and that in any conflict between the law and the Bible she would go with the Bible. As it happens, we spend more time reading religious tomes than do most people not in divinity school, and don’t recall any justification in any religious text, Eastern or Western, for driving under the influence. While we have no doubt that this woman considered herself to be a God-fearing pillar of her community, it seemed to us that in her disregard of civil society the difference between her view and that of a terrorist was a subtle one indeed, largely involving degree and opportunity, rather than belief.

For a more actualized example of faith gone awry, one has but to read the speeches of Adolph Hitler (http://www.hitler.org/speeches/) to understand the strength and depth of his underlying religious faith and feelings. Hitler was, by all accounts, a compelling speaker, and many were apparently moved when he said,

“Ich sage: Mein christliches Gefühl weist mich hin auf meinen Herrn und Heiland als Kämpfe. Es weist mich hin auf den Mann, der einst einsam, nur von wenigen Anhängern umgeben, diese Juden erkannte und zum Kampf gegen sie aufrief, und der, wahrhaftiger Gott, nicht der Größte war als Dulder, sondern der Größte als Streiter! In grenzenloser Liebe lese ich als Christ und Mensch die Stelle durch, die uns verkündet, wie der Herr sich endlich aufraffte und zur Peitsche griff, um die Wucherer, das Nattern- und Ottergezücht hinauszutreiben aus dem Tempel! Seinen ungeheueren Kampf aber für diese Welt, gegen das jüdische Gift, den erkenne ich heute, nach zweitausend Jahren, in tiefster Ergriffenheit am gewaltigsten an der Tatsache, daß er dafür am Kreuze verbluten. Als Christ habe ich nicht die Verpflichtung, mir das Fell über die Ohren ziehen zu lassen, sondern habe die Verpflichtung, ein Streiter zu sein für die Wahrheit und für das Recht.”

“I say: my feeling as a Christian points me to my Lord and Saviour as a fighter. It points me to the man who once in loneliness, surrounded only by a few followers, recognized these Jews for what they were and summoned men to the fight against them and who, god’s truth! was greatest not as sufferer but as fighter. In boundless love as a Christian and as a man I read through the passage which tells us how the Lord at last rose in His might and seized the scourge to drive out of the Temple the brood of vipers and of adders. How terrific was His fight for the world against the Jewish poison. Today, after two thousand years, with deepest emotion I recognize more profoundly than ever before – the fact that it was for this that He had to shed His blood upon the Cross. As a Christian I have no duty to allow myself to be cheated, but I have the duty to be a fighter for truth and justice.” Adolf Hitler from 12 April 1922 in the Munich Buergerbraeukeller.

While most would agree that this was perversion of Christ’s message, we nonetheless have no reason to doubt the depth and sincerity of Hitler’s religious convictions in 1922. Because of this, we think it should be a warning that broad faith-based initiatives, unfettered by ethical considerations, can be very dangerous for the world at large.

Religion-related terrorism

As a rule of thumb, today’s religion-related terrorism is a response to some perceived oppression or wrong or attack that cannot be corrected within the political process. In some cases it is a response to genocide by a religious majority, and in other cases the cause may be less apparent to the outsider. Since we have the examples of both Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, we know that there are effective alternatives to violence. Unfortunately, peaceful resistance did not make much of an impression on the thoughts of the majority of those who feel themselves to be oppressed.

We absolutely do not condone criminal violence against innocents, even when committed by people reacting to what they perceive as unfairness, and not even when their perception is based in fact. Even without the prospect of criminal violence, it is imperative – as well as prudent – that we examine what others with whom we deal say in order to see if there is a perception of wrongdoing on our part. If there is such a perception, we should see whether there is are ways to change their perception, which may require some policy change if the perception is based on fact. If we can change these perceptions, it may well reduce the likelihood of violence, and, thus, the death toll on both sides.

Criminal violence is never justified, even when on behalf of God. Thus, the U.S. Army – and therefore the United States – recognizes Satanism as a valid religion, but it does not condone human sacrifice. No perception of being oppressed; no human sacrifice; no problem. However, at the point where Satanism crosses over to crime (at a Satanism and Witchcraft luncheon we got to see a lot of morgue photos while we ate our rubber chicken), it must be dealt with.

What can be done to prevent religion-related terrorism?

Most faith-based initiatives, whether they are supplying warm coats for the needy during the winter, or running planes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, are an attempt to rectify a problem that is not being dealt-with by public social policy. This means that there is a public-policy opportunity to identify problems that are not being dealt-with, and to deal with them before they become a public danger, rather than merely dealing with the aftermath.

In looking at the current events, we note that bin Laden had been remarkably consistent over the years in outlining his objections to U.S. actions, including having non-Muslim soldiers on holy ground, support of corrupt Muslim leaders in countries like Saudi Arabia, forcing of Islam’s major resource (oil) to be sold at well below market value, support of countries that persecuted Muslims, et cetera. He incorrectly perceived these to indicate a deliberate attack on Islam, which therefore warranted violence against innocents. He was wrong: Few in the U.S. cared much about Islam one way or the other.

Right or wrong, we had a decade or more of his public pronouncements (eventually accompanied by escalating violence) about what he perceived as an attack against Islam, and yet we have heard no discussion as to our attempts to change his perception, and to make him realize that we were not involved in a new Crusade. Might some minor policy shift have kept bin Laden from saying, in 1998, that “The ruling to kill all Americans and their allies – civilian and military – is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it,” which most of the world considers to be a perversion of religion. (Note that bin Laden is not a religious scholar, and thus not empowered to issue a fatwa.)

Does this mean that we should be changing our public policy to match the whim of every religious loon on the planet? No, but it means that we need to be aware of possible misperceptions that we might be inadvertently exacerbating, and that we need to reduce or eliminate these misperceptions, and thus potential dangers, before they escalate. We believe that those who died on 9/11 – and those survived those who died – would have preferred for bin Laden not to feel impelled to build to this event.

Our intelligence services clearly have the expertise and experience to identify these issues. A quick read of Imperial Hubris by Anonymous (aka Michael Scheuer, published by Brassey’s Inc., ISBN: 1574888498, http://www.brasseysinc.com/Books/BookDetail.aspx?productID=89740) will show that there was institutional awareness of this issues, but no administrative support for using this knowledge to reduce tensions.

Keep in mind that the issues are not merely geopolitical. Every time we encounter a situation where a person of faith – no matter how misplaced – burns a cross on someone’s lawn, or burns down a church, or paints swastikas on a synagogue, or refuses to do business with a person of another faith, it is a problem related to religion that should have been identified and rectified.

Since it is usually cheaper to avoid a problem than to recover from it, and cheaper to prevent a crime than to solve it, we owe it to ourselves to at least add the perception of our actions by others to our public policy mix.

The underlying causes of religion-related violence (You can skip this part if you don’t care about the nuts and bolts of theology)

In this section we will concentrate on the religions of the West, and, more particularly, on Christianity and Islam, largely ignoring Judaism. Why do we ignore Judaism? We feel that the Jews lost all geopolitical power with the destruction of the first Temple at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar in 586 BC. They certainly lost their final vestige of power once and for all in 70 AD when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem: According to Josephus (The Wars of the Jews, Book 6, Chapter 9, Paragraph 3), 1.1 million Jews were killed in the city of Jerusalem and 97,000 were taken into captivity during the destruction of the city. By any reckoning, once there was no Temple on the Temple Mount – now better known as Haram-es-Sherif – the Jews were, no longer and never again, a group of real geopolitical significance. This was made clear in 638 AD, when Umar I commissioned a mosque on the Temple Mount (site of the destroyed First and Second Temples) to demonstrate Moslem hegemony over Jerusalem’s Jewish and Christian holy sites, as well as to commemorate the Night Journey wherein Mohammad, accompanied by the Archangel Gabriel, flew of an evening (on Al-Buraq – White Horse, but read as Lightning – a winged, horse-like creature that was smaller than a mule, but larger than a donkey) the 765 miles from Mecca to Jerusalem (stopping at Mount Sinai and Bethlehem), returning to Mecca before dawn.

Revealed religions

An underlying cause of religion-related violence springs from the fact that the major religions of the West are revealed religions, which is to say that the Word of God is revealed to someone directly. The problem is that while you accept that the revelation that underlies your beliefs comes directly from God, this means that beliefs that contradict or differ from yours must come from some source other than God. These other sources are therefore questionable at best: There are, after all, a lot of burning bushes, and anyone from Southern California can tell you that they don’t all have your best interest at heart.

The implication of this is rather clearly explained in the Catholic Encyclopedia, which notes (they are speaking of the Inquisition, but the concept is extensible) that moderns have forgotten two facts:

“On the one hand they have ceased to grasp religious belief as something objective, as the gift of God, and therefore outside the realm of free private judgment; on the other they no longer see in the Church a society perfect and sovereign, based substantially on a pure and authentic Revelation, whose first most important duty must naturally be to retain unsullied this original deposit of faith. Before the religious revolution of the sixteenth century these views were still common to all Christians; that orthodoxy should be maintained at any cost seemed self-evident.”

If you substitute “Islam” for “the Church” you understand why some contemporary Muslims, who have not gone through a reformation, can so ferociously fight for their beliefs: They still see in Islam a society perfect and sovereign, based substantially on a pure and authentic Revelation, whose first most important duty must naturally be to retain unsullied this original deposit of faith. They therefore behave toward Unbelievers in a way that those of us who have studied pre-Reformation Christianity might think of as being, in the words of Yogi Bera, “déjà vu all over again.”

The role of monotheism in decreasing religious tolerance

Another problem is that Christianity and Islam are monotheistic religions. With polytheism, it is widely recognized that there are multiple Gods, and that you can choose those that suit your purpose. This allows for a lot of tolerance. Others may think you silly to choose Thor over Odin, or Mars over Venus, or to worship a spruce over an oak, but they recognize your right to choose.

Monotheism, on the other hand, generally recognizes the existence of multiple Gods, but requires you to choose one. Thus, the Ten Commandments of the ancient Hebrews says,

ρσα ενφμτ λκφ λξπ κλ εσοτ αλ

“Thou shalt have no other gods before Me.”

The Latin Vulgate Bible of Saint Jerome says,

“non habebis deos alienos coram me”

“Thou shalt not have strange gods before me.”

Islam makes a break from the Judeo-Christian model, and says that there is one God, rather than many from which one must choose. While the thought is repeated many times throughout the Qur’an, we will include only two, giving three alternative approximations for each passage, to give those who don’t read Arabic a better sense of the text.

In 002.163 the Qur’an says:

And your Allah is One Allah: There is no god but He, Most Gracious, Most Merciful.

or

Your Allah is One Allah; there is no Allah save Him, the Beneficent, the Merciful.

or

And your Allah is one Allah! there is no god but He; He is the Beneficent, the Merciful.”

And in 003.002

“Allah! There is no god but He,-the Living, the Self-Subsisting, Eternal.

or

Allah! There is no god save Him, the Alive, the Eternal.

or

Allah, (there is) no god but He, the Everliving, the Self-subsisting by Whom all things subsist.”

Once a religion makes other Gods “bad,” the way is opened up for actions appropriate to their badness.

Religious choice

In theory choice of religion should be just that: A choice. As the Catholic Encyclopedia notes:

“Force, violence, or fraud may not be employed to bring about the conversion of an unbeliever. Such means would be sinful. The natural law, the law of Christ, the nature of faith, the teaching and practice of the Church forbid such means. Credere voluntatis est, to believe depends upon the free will, says St. Thomas (II-II:10:8), and the minister of baptism, before administering the sacrament, is obliged to ask the question, “Wilt thou be baptized”? And only after having received the answer, “I will”, may he proceed with the sacred rite. The Church also forbids the baptism of children of unbaptized parents without the consent of the latter, unless the children have been cast away by their parents, or are in imminent danger of death. For the Church has no jurisdiction over the unbaptized, nor does the State possess the power of using temporal means in spiritual things.”

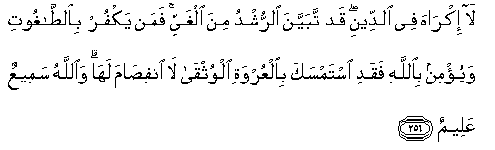

And the Qur’an says in 002.256

“Let there be no compulsion in religion: Truth stands out clear from Error: whoever rejects evil and believes in Allah hath grasped the most trustworthy hand-hold, that never breaks. And Allah heareth and knoweth all things.

or

There is no compulsion in religion. The right direction is henceforth distinct from error. And he who rejecteth false deities and believeth in Allah hath grasped a firm handhold which will never break. Allah is Hearer, Knower.

or

There is no compulsion in religion; truly the right way has become clearly distinct from error; therefore, whoever disbelieves in the Shaitan and believes in Allah he indeed has laid hold on the firmest handle, which shall not break off, and Allah is Hearing, Knowing.”

We really don’t know what the Jews did in the 370 years before the destruction of the first Temple in 587 BC, but the Encyclopedia Britannica indicates that during at least the third century BC Jews were enthusiastic proselytizers (from προσήλυτος, meaning one who has found their place).

Muslims are enthusiastic proselytizers, and have definite ideas about the place (and treatment) of nonbelievers. The Pact of Umar (http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/pact-umar.html) is attributed to the second Caliph, Umar 1 (circa 586-644, although the current version of the Pact likely comes from the 9th century), and formed the standard for compassionate (by the standards of that time) treatment of Dhimmi (protected persons) in occupied territories.

The view of some Christians toward non-Christians, or Christians of other sects, is not all that different from that of some Jews or Muslims. We know of a case a man won the bid on a contract. As they were about to close the deal the person issuing the contracting said, “I forgot to ask. You are a …, aren’t you?” When the bidder said that no, he belonged to a different sect, the man said, “I’m sorry, but I wouldn’t feel comfortable doing business with someone who isn’t a …,” swept the papers into his briefcase, and walked out.

This is not an isolated case. It is traditional in certain areas for grade school teachers to ask their students, on the first day of school, who had gone to Christian camp. Those who say yes are put into the front row, bumping those who were there toward the back.

In a third example, a participant in a law enforcement conference was asked what he liked most about the conference. His answer was not anything to do with the content of the course. Rather, it was that he got to spend a lot of time with good Christian gentlemen.

Choosing your own revelation

Unfortunately, while early religious dicta might speak of free choice, you don’t have to go very far down the religious food chain to reach folks who still hold the belief that “orthodoxy should be maintained at any cost.” More unfortunately, the beliefs of those trying to maintain the orthodoxy may be a trifle off the mark of what God intended. Sometimes this can be caused by something simple as a typographical error. As an example, the Dead Sea Scrolls indicate that in the 23rd Psalm God set a shield in the sight of mine enemies, not a table, which is one letter different, and undoubtedly a mistake by some overtired copyist.

An additional factor is that the Bible is now individually interpreted, with some acting on snippets convenient to their beliefs. (Some Muslims outside the Ulama – the community of learned men – have done the same with the Qur’an.)

Thus, we recently watched a television discussion of abortion between representatives of two Christian groups, one of which opposed abortion on religious grounds and the other of which supported abortion on religious grounds, in which each side produced convincing Biblical references to support their position. The person supporting abortion had a scriptural passage that indicated that God considered an unborn child to be less valuable than someone who had been born. The opponent was familiar with the passage, and noted that the passage before supported slavery, and asked whether his opponent supported slavery. The politically correct answer was, of course, no. Logically, this makes no sense: If God scripturally supports slavery, then slavery should be as acceptable as the view in favor of – or against – abortion. The bottom line is that people choose those passages of the Bible or Qur’an which supports their case, and then act on them.

The following set of questions about the Old Testament, which have been circulating on the Internet for some years, amusingly points out the problem we moderns face in strictly accepting the Word of God.

“When someone tries to defend the homosexual lifestyle, for example, I simply remind them that Leviticus 18:22 clearly states it to be an abomination…End of debate. I do need some advice from you, however, regarding some other elements of God’s Laws and how to follow them.

1. Leviticus 25:44 states that I may possess slaves, both male and female, provided they are purchased from neighboring nations. A friend of mine claims that this applies to Mexicans, but not Canadians. Can you clarify? Why can’t I own Canadians?

2. I would like to sell my daughter as a maidservant, as sanctioned in Exodus 21:7. In this day and age, what do you think would be a fair price for her?

3. I know that I am allowed no contact with a woman while she is in her period of menstrual uncleanliness – Leviticus 15: 19-24. The problem is how do I tell? I have tried asking, but most women take offense.

4. When I burn a bull on the altar as a sacrifice, I know it creates a pleasing odor for the Lord – Leviticus 1:9. The problem is, my neighbors. They claim the odor is not pleasing to them. Should I smite them?

5. I have a neighbor who insists on working on the Sabbath. Exodus 35:2.clearly states he should be put to death. Am I morally obligated to kill him myself, or should I ask the police to do it?

6. A friend of mine feels that even though eating shellfish is an abomination – Leviticus 11:10, it is a lesser abomination than homosexuality. I don’t agree. Can you settle this? Are there ‘degrees’ of abomination?

7. Leviticus 21:20 states that I may not approach the altar of God if I have a defect in my sight. I have to admit that I wear reading glasses. Does my vision have to be 20/20, or is there some wiggle-room here?

8. Most of my male friends get their hair trimmed, including the hair around their temples, even though this is expressly forbidden by Leviticus 19:27. How should they die?

9. I know from Leviticus 11:6-8 that touching the skin of a dead pig makes me unclean, but may I still play football if I wear gloves?

10.My uncle has a farm. He violates Leviticus 19:19 by planting two different crops in the same field, as does his wife by wearing garments made of two different kinds of thread (cotton/polyester blend). He also tends to curse and blaspheme a lot. Is it really necessary that we go to all the trouble of getting the whole town together to stone them? Couldn’t we just burn them to death at a private family affair, like we do with people who sleep with their in-laws? (Leviticus 20:14)”